Chapter 5 Axioms and definitions

Now that we fully understand what makes a statement “mathematical,” we should discuss axioms and definitions.

5.1 Axioms are a special kind of mathematical statement

Axioms are mathematical statements which are true, and are self-evidently so and therefore cannot be proved. They should be things so obviously true or so universally accepted, that when you read them, you say to yourself, “Duh, of course!”11. Axioms should be so obvious, that when asked to prove them, you end up scratching your head and shouting “C’MON, IT JUST IS TRUE!!!!”

Axioms are the building blocks of mathematics. There is no complete list of them all, as we can always add more of them to the list. This chapter contains the axioms which we may use in this course. Tell me if you find a statement which you believe is an axiom but which I’ve forgotten, and I’ll add it to the list below.

5.1.1 Rules of axioms

- Axioms describe a property of a mathematical object or operation.

- Axioms should never cover more than one property.

- The property each axiom describes is not necessarily unique to the mathematical object, for example the commutativity property is true for both multiplication, “\(ab = ba\),” and addition, “\(a+b=b+a\).” Similarly “There are infinitely many ways to cut a circle into two equal halves” is also true for spheres: “There are infinitely many ways to cut a spheres into two equal halves.”

- Axioms are mathematical statements which are true, elementary and universally accepted, but which don’t have proofs (because they are so fundamental).

- Axioms should not be derived from other axioms.

5.1.2 Axioms about algebra

Here are a few axioms about algebra. Note that \(a, b, c\) and \(d\) can be any numbers.12

- If \(a = c\) then \(c = a\).

- If \(a = c\) and \(b = c\), then \(a = b\).

- If \(a = b\) and \(b = c\), then \(a = c\).

- If \(a = b\) and \(c = d\), then \(a + c = b + d\).

- \(a \cdot b = b \cdot a\).

- If \(a = b\) and \(c = d\), then \(ac = bd\).

5.1.3 Axioms about geometry

Here are a few axioms about geometry.13 Look up any words you don’t understand.

- If you have two points, you can draw a straight line which connects them.

- If you have two points, you can always draw a circle with one of the points at the circle’s centre and the other on its edge.

- There are infinitely many ways to cut a circle into two equal halves.

- A straight line can be extended in either direction forever.

- Three points can be arranged in such a way that they don’t all lie on the same straight line.

- Four points can be arranged in such a way that they don’t all lie on the same flat plane.

Note: All of these axioms above can be written in even briefer terms, though I haven’t done so, in order to ensure clarity.

Exercise 5.1 Illustrate each of the six geometric axioms above with a pictorial example.

Exercise 5.2 Can you think of any more algebraic or geometric statements which you believe are so obviously true that they are in fact axioms. Suggest them to me and if they’re axioms, I’ll add them to this chapter.

It’s possible that you might consider a statement to be an axiom (something so obviously true that no proof is needed), but someone else might believe it is not self-evident and that a proof is needed.

That’s fine…if challenged to prove something that you believe is an axiom, rise to that challenge!

5.2 Definitions are a special kind of axiom

Where axioms describe a property of a mathematical object or operation, definitions describe mathematical objects or operations themselves. If axioms form the rulebook of mathematics, then definitions form the dictionary of mathematics.

5.2.1 Rules of definitions

- Definitions describe a mathematical object or operation.

- Definitions should never cover more than one object or operation.

- Mathematical objects or operations don’t have to have just one possible definition (e.g. the meaning of multiplication changes if we’re talking about scalars, vectors, matrices, etc.).

- Definitions answer the question, “What is a …?” for example “What is a square” or “What is an even number?” or “What is multiplication?”

- Definitions can’t be proved, they are just accepted by all people doing mathematics.

- Definitions allow us to all agree on key terms in mathematics.

- Definitions can refer to other definitions.

Exercise 5.3 Write definitions for the following objects or operations.

- A square number (or perfect square).

- A whole number (or integer).

- A non-whole number.

- Consecutive whole numbers.

- One number divides another. (Careful here, I don’t simply mean division. Consider that 4 divides 12 but that 5 does not divide 12.)

- An even number.

- An odd number.

- The absolute (or modulus) operation.

- A point.

- A line.

Solution. These are my definitions, but these are not perfect. Different people might choose different words to describe these things, and your definitions might look different to mine. This isn’t a problem as long as our definitions are both clear, and we both mean the same thing!

- A square number (or perfect square) is the square of a whole number.

- Whole numbers (or integers) are numbers with digits only to the left of the decimal point.

- Non-whole numbers are numbers which have value to the right of the decimal point (and possibly to the left too).

- Two whole numbers \(a\) and \(b\) are consecutive if either \(b = a + 1\) or \(a = b + 1\).

- \(a\) divides \(b\) if \(b \div a\) leaves no remainder.

- Even numbers are whole numbers which can be written in the form \(2n\), where \(n\) is a whole number.

- Odd numbers are whole numbers which cannot be written in the form \(2n\), where \(n\) is a whole number.14

- The absolute (or modulus) of a negative number is the positive version of that number.

- A point has no length, width or height.

- A line has length but no width or height.

Exercise 5.4 Below are three mathematical statements (i.e. they have clearly-defined truth values). One of them is an axiom, one is a definition and one is just a regular statement. Which is which?

- The sum of the digits of any number divisible by \(9\) is itself divisible by \(9\).

- The product of two negative numbers is positive.

- For two positive numbers \(a\) and \(b\), \(a\) is larger that \(b\) if \(a - b > 0\).

Exercise 5.5 Come up with definitions of the following terms. Try to be concise, but sufficiently clear.

- A rectangle.

- A square.

- A straight line.

- A circle.

- A 3D shape.

- A rational number.

- Consecutive even numbers.

- Consecutive odd numbers.

- MAX( ).

- MIN( ).

- An acute angle.

- A circle’s circumference.

- A tangent to a circle.

- The sum of two numbers.

- The difference of two numbers.

- The product of two numbers.

- The ratio of two numbers.

- A cube number (or perfect cube).15

- A triangle.

- A cuboid.

- Adjacent sides of a triangle.

- A multiple of a number.

- An octagon.

- Two perpendicular lines.

- A prime number.

- The proper divisors (or proper factors) of a whole number.

Solution. 16

A square number (or perfect square) is the square of a whole number.

Whole numbers (or integers) are numbers with digits only to the left of the decimal point.

Non-whole numbers are numbers which have value to the right of the decimal point (and possibly to the left too).

Two whole numbers a and b are consecutive if either \(b = a + 1\) or \(a = b + 1\).

\(a\) divides \(b\) if \(b ÷ a\) leaves no remainder.

Even numbers are whole numbers which can be written in the form \(2n\), where \(n\) is a whole number.

Odd numbers are whole numbers which cannot be written in the form \(2n\), where \(n\) is a whole number.

The absolute (or modulus) of a negativenumber is the positive version of that num-ber.

A point has no length, width or height.

A line has length but no width or height.

A rectangle: A 2D shape with four straight sides and four right angles

A straight line: a line with unchanging slope

A circle: a shape representing all the points equidistant from a single point

A 3D shape: a shape with width, length and height

A rational number: a number that be expressed at the ratio of two integers

Consecutive even numbers: If a is an even number \(2n\), and \(b = a+2\), then \(a\) and \(b\) are consecutive even numbers.

Consecutive odd numbers: If \(a\) is an odd number \(2n + 1\), and \(b = a + 2\), then \(a\) and \(b\) are consecutive odd numbers.

MAX( ): Returns the largest of a set of numbers.

MIN( ): Returns the smallest of a set of numbers.

An acute angle: An angle measuring between \(0\) and \(90\) degrees.

A circle’s circumference: The distant around the edge of a circle.

A tangent to a circle: A straight line which intercepts a circle only once.

The sum of two numbers: For two numbers \(a\) and \(b\), their sum is \(a + b\).

The difference of two numbers: For two numbers \(a\) and \(b\), their difference is \(a - b\).

The product of two numbers: For two numbers \(a\) and \(b\), their product is \(a \cdot b\).

The ratio of two numbers: For two numbers \(a\) and \(b\), their ratio is \(a / b\).

A cube number (or perfect cube): A perfect cube is the cube of an integer.

A triangle: A three-sided 2D shape.17

A cuboid: A 3D shape which has six rectangular faces at right angles to each other.

Adjacent sides of a triangle: Two sides which meet at a common point.

A multiple of a number: The number multiplied by any integer.

An octagon: An eight-sided 2D shape.

Two perpendicular lines: Two straight lines which meet at a right-angle.

A prime number: An integer whose only two unique divisors are \(1\) and itself.

The proper divisors (or proper factors) of a whole number: Integers which divide into another integer, excluding the number itself.

Exercise 5.6 Use the following questions to check your understanding of some key definitions.

- Is zero even?

- Is a square a rectangle?

- Does \(12\) have five or six divisors?

- How many proper divisors does \(25\) have?

- If a triangle is a “\(3\)-gon,” a pentagon is a “\(5\)-gon,” and an octagon is an “\(8\)-gon,” what is a “\(4\)-gon?”

- What’s a “\(6\)-gon?” What’s a “\(2\)-gon?”

- Is \(87\) prime?

- How many multiples of \(7\) are two-digit numbers?

- How many pairs of adjacent sides does a triangle have?

- How many of the following are not lengths?

- circumference of a circle

- perimeter of a rectangle

- distance between two points

- width of a cuboid

- height of a cylinder

5.3 Types of real numbers

In section 5.4, we will meet some axioms about inequalities. Inequalities describe the ordering of real numbers. In this section, we will check we know what real numbers are.

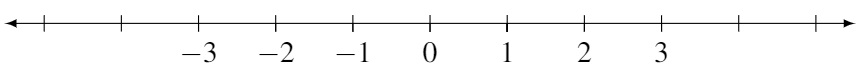

Real numbers are any numbers on the number line which stretches from \(-\infty\) to \(\infty\):

Figure 5.1: The number line.

Any number that a calculator can display is a real number:

- Whole numbers (integers)

- Terminating decimals (0.1, -0.5, 68.25)

- Recurring decimals (\(\frac{1}{3} = 0.3333...\), \(-\frac{11}{9} = -1.2222...\), \(\frac{1}{7} = 0.142857142857...\). In the last example, notice that the sequence \(142857\) repeats.)

- Non-recurring decimals (\(\pi = 3.1415926...,\) \(e = 2.7182818284590\), \(\sqrt{2} = 1.41421356237...\))

We split the four types of real number above into two groups:

5.3.1 Rational real numbers

(A), (B) and (C) are rational real numbers, because they can be expressed as the ratio of two integers.

Exercise 5.7 Pick an example of a number of type (A), (B) and (C) above. Show for each of your choices that the number can be written as the ratio of two integers.

5.3.2 Irrational real numbers

Type (D) are irrational real numbers, because they can’t be written as the ratio of two whole numbers.

5.3.3 Symbols

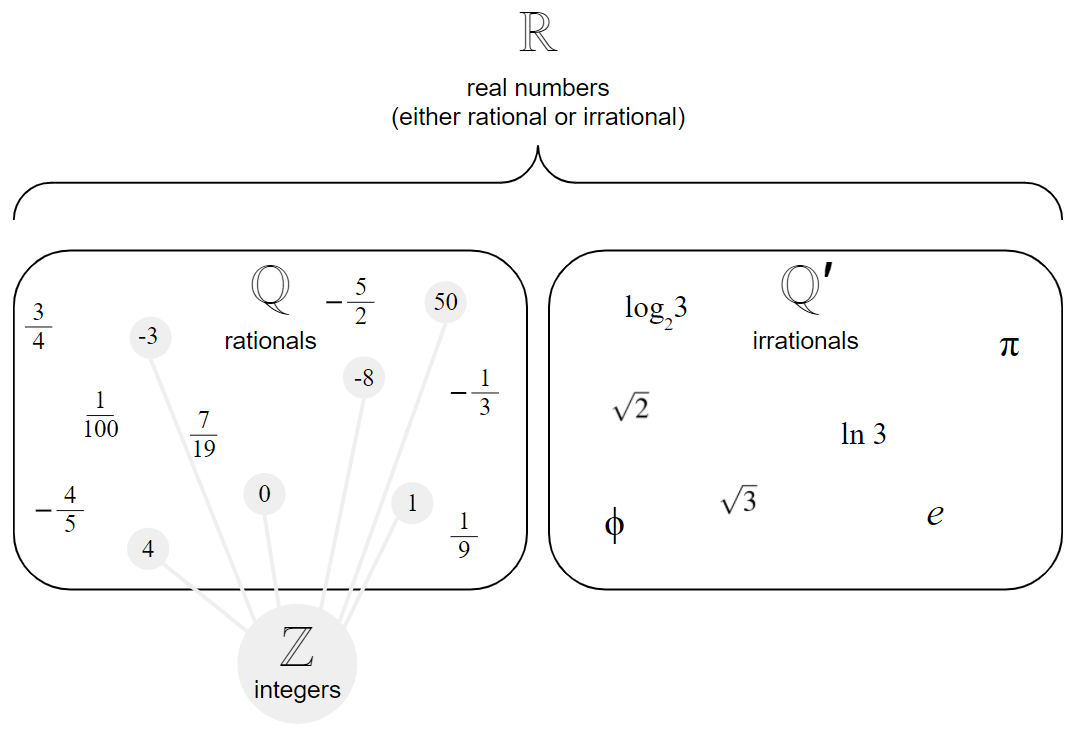

We use the symbol \(\mathbb{R}\) to mean ALL real numbers, for example \(a \in \mathbb{R}\) means that the number \(a\) is a real number (and \(a \not\in \mathbb{R}\) means that the number \(a\) is not a real number20).

We use the symbol \(\mathbb{Q}\) for just the rational real numbers, and \(\mathbb{Q}'\) for the non-rational real numbers. For those rational numbers which are integers (whole numbers), we use the symbol \(\mathbb{Z}\).

Figure 5.2: The real numbers are divided into two groups.

How to use these symbols? As mentioned above, to tell your reader that you’re talking about a general real number, you write \(a \in \mathbb{R}\), where \(\in\) means “belongs to” or “is.”

Careful!

The symbol \(\in\) is very powerful: it covers ALL possible values of the type of number given. For example, if you write \(a \in \mathbb{Z}\), you are saying that \(a\) could be any integer in the world, and if you write \(a \in \mathbb{Q}\), you’re saying that \(a\) can be any rational number. Similarly, writing \(a \in \mathbb{Q'}\) means that \(a\) is any irrational number (so not just \(\pi\) or \(\sqrt{2}\)).

Add \(^{+}\) to any symbol to specify you’re only talking about the positive numbers from the set. Similarly, add \(^{-}\) to specify you’re only talking about the negative numbers from the set.

Exercise 5.9 Give a couple of examples of \(a\) in each of the cases below.

- \(a \in \mathbb{Z}^{+}\)

- \(a \in \mathbb{Q}'\)

- \(a \in \mathbb{Q}^{+}\)

- \(a \in \mathbb{Z}^{*}\)

- \(a \in \mathbb{Z}^{-}\)

- \(a \in \mathbb{R}\)

- \(a \in \mathbb{C}\)

- \(a \in \mathbb{Z}\)

- \(a \in \mathbb{R}^{+}\)

Part d might be more challenging!

5.3.4 Further dividing up the integers

Within the integers, there are lots of sets of special numbers, for example even numbers, odd numbers, prime numbers, triangle numbers, Fibonacci numbers, and perfect numbers. Some of these sets overlap (i.e. there are some numbers which are in more than one set).21

Exercise 5.10 Can you find:

- A number which is both prime and triangular?

- A number which is both prime and perfect?

- A number which is both triangular and perfect?

Exercise 5.11 Are there any prime Fibonacci numbers?

Exercise 5.12

- Is 1 perfect? Triangular? Prime? A Fibonacci number?

- Is 2 perfect? Triangular? Prime? A Fibonacci number?

Exercise 5.13 What’s the smallest positive integer that is neither prime nor triangular nor perfect nor Fibonacci?

5.4 Inequalities

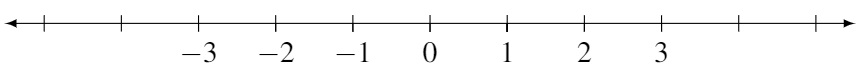

Inequalities compare numbers22, in terms of their size. Earlier in this chapter we defined “greater than” and “less than.” One number is “greater than” another if it appears further to the right on the number line:

Figure 5.3: The number line. The further to the right a number is, the ‘greater’ it is.

So \(11\) is greater than \(10\) (or \(11 > 10\)), and \(10\) is greater than \(0\) (or \(10 > 0\)), and \(2 > -5\) and \(-5 > -10\). If we write \(a > 5\), we mean that \(a\) is a number greater than \(5\) (for example \(6\) or \(20\) or \(5.1\)). If we write \(a \geq 5\) we mean \(a\) is either greater than \(5\) or equal to \(5\). The symbols \(<\) and \(\leq\) apply for less than, and less than or equal to.

Exercise 5.14 Here are three axioms about inequalities:

- If \(a>0\) and \(b>0\), then \(a+b>0\).

- If \(a>0\) and \(b>0\), then \(ab>0\).

- If \(a>0\) and \(b>0\), then \(a + b > a\) and \(a + b > b\).

Because these are axioms, we can’t prove them (they are too fundamental). However, we can illustrate them with examples. Find examples of each of the axioms above, in order to illustrate them.

Exercise 5.15 Aida says that, mathematically, \(-10\) is greater than \(-50\). Murat says that \(-50\) could be considered as greater than \(-10\), in certain circumstances. How could you argue Murat’s case? Give specific example(s) how he could be seen as right.23

Exercise 5.16 Below are five more axioms about inequalities. Again, illustrate each of these axioms with an example.

- If \(a > b\) and \(k\) is any real number, then \(a + k > b + k\).

- If \(a > b\) and \(b > c\), then \(a > c\).

- If \(a > b\) and \(k > 0\) then \(ak > bk\).

- If \(a > b\) and \(k < 0\), then \(ak < bk\).

- For any real number \(a\), \(a^2 \geq 0\).

Exercise 5.17 Below are four conjectures about inequalities. Find counterexamples which disprove them:

- If \(a>0\) and \(b>0\), then \(ab > a\) and \(ab > b\).

- If \(a^2 < b^2\) then \(a < b\).

- If \(a < b\) and \(k < l\) then \(ak < bl\).

- If \(\dfrac{a}{b} > cd\) then \(ad > bc\).

You only need to find one counterexample for each. Hint: Negative numbers will be useful here!

See https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Foundations_of_geometry, http://web.mit.edu/wwmath/vectorc/3d/old/axioms.html, https://www.ams.org/journals/tran/1904-005-03/S0002-9947-1904-1500678-X/S0002-9947-1904-1500678-X.pdf, and http://www.mrc.uidaho.edu/~rwells/Critical%20Philosophy%20and%20Mind/Chapter%2023.pdf.↩︎

Alternatively: Odd numbers are whole numbers which can be written in the form \(2n + 1\), where \(n\) is a whole number.↩︎

Unlike perfect squares, perfect cubes do not have a small number of possibilities for the last two digits. Except for cubes divisible by \(5\), where only \(25\), \(75\) and \(00\) are allowed.↩︎

See https://studymaths.co.uk/glossary.php, http://www.mrc.uidaho.edu/~rwells/Critical%20Philosophy%20and%20Mind/Chapter%2023.pdf, https://www.quora.com/Is-there-a-comprehensive-list-of-axioms-and-math-principles-to-make-learning-math-easier, https://sites.math.washington.edu/~aloveles/Math300Summer2011/Math300Axioms.pdf.↩︎

According to this song, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=gHjnGbNBuAw, “three points were two lines meet.”↩︎

Rational and irrational numbers have very different properties. The digits of rational numbers (including non-terminating decimal numbers) are fully known. The digits of irrational numbers can’t be fully known because they follow no pattern and don’t repeat. Just because you know the first 12 million decimal digits of \(\pi\), it doesn’t mean you can predict the 12-million-and-first digit!↩︎

Whilst \(\pi\) and \(e\) are both known to be irrational, no one knows if \(\pi + e\), \(\pi e\), \(\dfrac{\pi}{e}\), \(\pi^e\), \(\pi^\pi\), \(e^e\), \(e^\pi\), \(2^e\) or ln\(\pi\) are rational or irrational. See https://math.ou.edu/\char`\~jalbert/courses/openprob2.pdf.↩︎

We won’t deal with “non-real” numbers (called imaginary or complex numbers) in this course.↩︎

Within these sets, there are even smaller subsets of numbers. For example, the Mersenne primes are special examples of primes.↩︎

Or expressions↩︎

Note, in this course, we will ALWAYS use “greater than” to mean “further to the right on the number line” (despite what Murat says!).↩︎