Chapter 6 Mathematical proof

6.1 Mathematics versus other fields

Mathematical proof is different to proof in other fields. Let’s look at how.

6.1.1 Terminology

Mathematics has a different set of terms when talking about proofs.

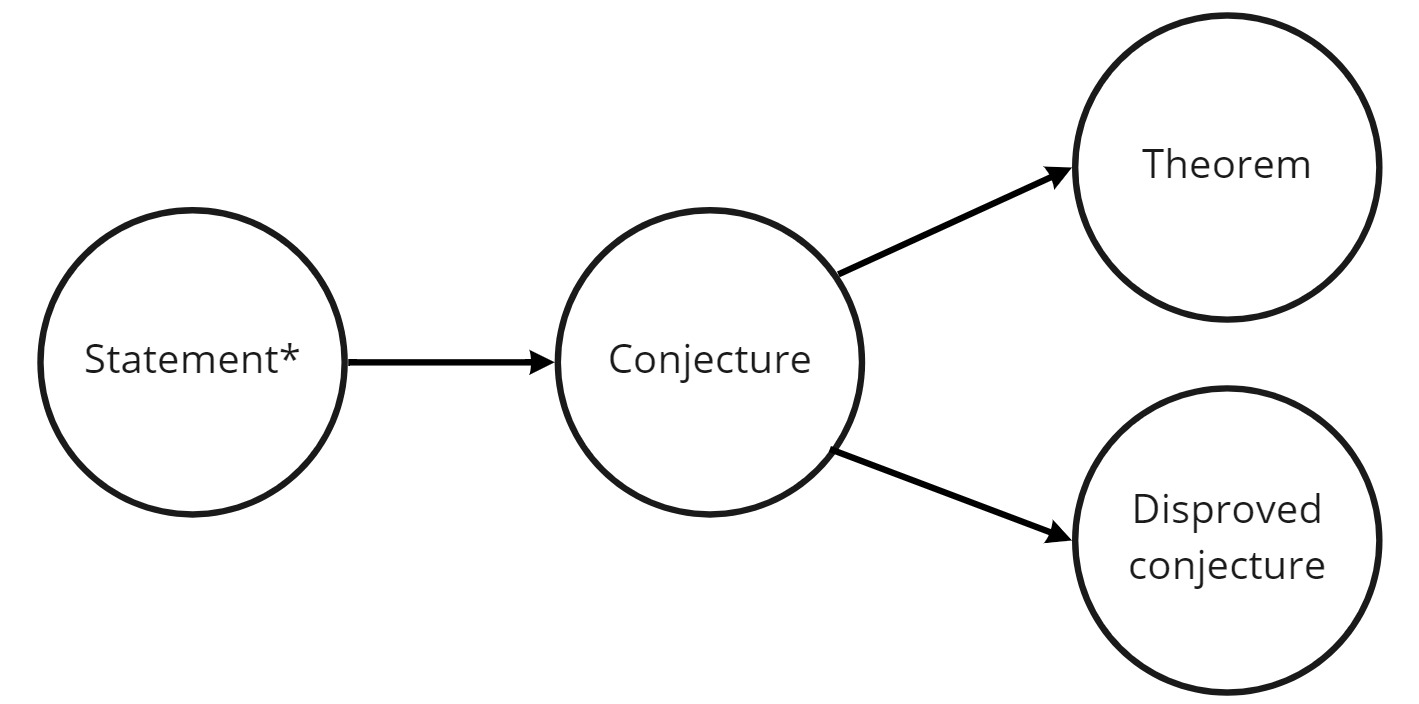

In mathematics, once we have identified a statement which we would like to try to prove or disprove, we rename it a conjecture.

If we are successful in proving it, the conjecture is renamed a theorem. If it is disproved, it is called a disproved conjecture. Only statements that have been proved true can be called theorems.

Figure 6.1: The journey of a statement.

* A mathematical statement obviously!

6.1.2 Methodology

In mathematics we talk about theorems. In other sciences, they talk about theories. What’s the difference? It all about how the proof is constructed.

A proof in mathematics must be built DEDUCTIVELY

We say therefore that a theorem in mathematics is deductively true. In other words, you should be able to provide a list of steps which someone else could follow and arrive at the same conclusions.

A proof in science is built on EVIDENCE

We say therefore that a scientific theory is empirically (or “verifiably”) true, based on observations made or evidence collected. To verify it, someone would need to either trust your evidence, or be able to recreate the evidence themselves.24 The Oxford English Dictionary defines a theory as “A statement of what are held to be general laws, principles or causes of something known or observed.”

That’s the difference between a theorem in mathematics and a theory in science.

6.1.3 Trial and improvement

In mathematics, once a conjecture’s truth value has been discovered, it remains this way forever. However in other sciences (both natural sciences and social sciences), theories are always being improved upon and added to as more research is done and more discoveries made.

This is a key principle of modern science - it doesn’t claim to know all the answers, but its aim is the truth, and it chooses as its foundations those theories which have the most compelling evidence.25

The theory of gravity, the theory of relativity, the theory of evolution and even the current form of the periodic table are all examples of theories which are constantly being changed and updated as new evidence is revealed.

Some scientific theories have even been shown to be completely wrong. Here’s a short list of some theories previously believed true but later disproven: https://www.famousscientists.org/10-most-famous-scientific-theories-that-were-later-debunked.

6.1.4 An ever-changing world

Statements about world geography, international politics, currency markets, individual people, the state of technology and a lot else besides are all likely to all be time-dependent. Countries fall, empires collapse, capitals change, phones get faster, people and animals evolve.

For example, the statement “Nur-Sultan is the capital of Kazakhstan” has a built-in time limit. It won’t be true forever. We don’t know how long it will be true for, but it won’t be true forever. Sure, it is true at the moment, but what if the capital is renamed in future years? The truth value of the statement would change.

“The capital of Kazakhstan is located in the north of the country” is also currently true. This statement is definitely more general, but is still time-dependent: the capital of Kazakhstan used to be located in the south of the country; what’s stopping the location of the capital city shifting again in the future?

And how long will Kazakhstan exist? All countries change over time. Eventually there won’t be a Kazakhstan, or a France or a Benin or a Britain.

6.2 So what does this all mean?

It means that the study of mathematics is different to other sciences, to economics, to philosophy, psychology, evolutionary biology, and all other fields of study. If something is proved in mathematics, its truth value won’t change over time. Prove something is true in mathematics and you know that it has always been true and that it will remain true forever.26 In 5 years or 100 years or 1000 years or a million years, the truth value will be unchanged.

The axioms laid down by the Greek mathematician Euclid of Alexandria over two thousand years ago, some of which you met in Chapter 5, are as true now as they were then.27

The mathematical proofs of the mathematician Muhammad ibn Musa al-Khwarizmi, born near Khiva in Central Asia, which he presented in his book The Compendious Book on Calculation by Completion and Balancing,28 have not had their truth values changed in the hundreds of years since. The many proofs of French mathematician Sophie Germain are as valid now as they were in the 18th and 19th century when she wrote them. The mathematics of American mathematician Katherine Johnson in the 1960s or the Iranian mathematician Maryam Mirzakhani in the 2000s and 2010s will remain relevant forever.

Anything You prove true in this course will be true forever. Anything you show is false will be false forever. Get ready to make your mark on history!

Something known as reproducibility.↩︎

This approach provides a stable platform for further exploration. Just because science can’t definitively say whether a statement is 100% true, its chosen approach is better than throwing our hands up and saying “who knows!” or “no one can be sure!” Considering that we have science to thank for iPhones, vaccinations against deadly diseases, increased food yields, an understanding of how all life on Earth is connected, space exploration, and a great many other things, it’s a pretty good approach!↩︎

For example, proving Pythagoras’ Theorem (https://www.pinterest.com/pin/300122762659059179/) tells us this theorem is true for all time.↩︎

See https://plus.maths.org/content/maths-minute-euclids-axioms.↩︎

The title of this book gave the us the word algebra, from the Arabic word al-jabr meaning “restoration,” “the reunion of broken parts” or sometimes “bone-setting.”↩︎